Borgata v. Phil Ivey: The Alleged Edge Sorting, Explained

Fans of real-life gambling stories may be wondering exactly how professional poker player Phil Ivey and a sharp-eyed accomplice are alleged to taken advantage of subtle variations in the playing cards being used at New Jersey’s Borgata Hotel Casino & Spa. The cards themselves, along with the card-identification technique called “edge sorting,” rest at the heart of a civil fraud lawsuit filed by the Borgata last week against Ivey and three other parties.

As we reported in our previous feature on the unfolding Borgata-v-Ivey case, Ivey played a variation of high-stakes baccarat at the Borgata on four different occasions betweem April and October of 2012, winning more than $9.6 million overall. As that fourth and final session concluded, Ivey was publicly identified as being involved in a big-money dispute with another major casino, London’s Crockfords Casino, involving another form of baccarat and what later turned out to be very similar edge-sorting allegations.

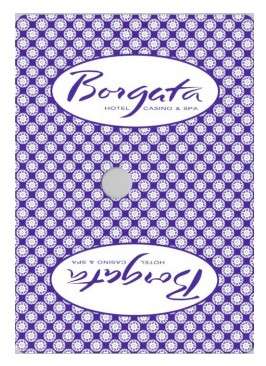

While court documents in the British case filed by Ivey against Crockfords have never been made public, last week’s lawsuit by the Borgata against Ivey contains an exact image of the “full bleed” card design being used on the card decks at the Borgata’s high-stakes baccarat tables. The cards were manufactured by a Missouri cardmaker, Gemaco, which is one of several major card manufacturers serving the gaming industry.

Gemaco and an unnamed “Jane Doe” employee of the company are also named in the Borgata lawsuit, as part of the inference made in the Borgata’s assertions that only because the cards were defective that Ivey and his companion, a sharp-eyed woman named Cheng Yin Sun (also named with Ivey in the Borgata suit), were able to identify them and cause them to be manipulated for identification purposes.

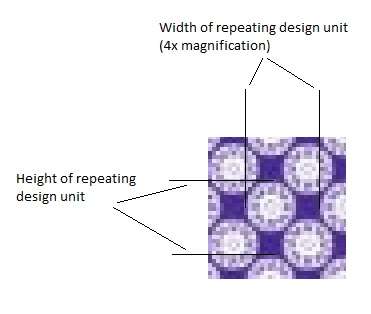

Much of this case will hinge on the cards themselves, so it’s important to understand how the alleged edge sorting supposedly happened. Here’s the image of the purple-blue Gemaco card with a customized, full-bleed “Borgata” design that was submitted to the court as a part of the Borgata’s filing:

This is the Borgata card design allegedly exploited by Phil Ivey to win over $9.6 million at the New Jersey casino.

The term “full bleed” refers to any card design that runs right off the edges of the card. The opposite would be a “no bleed” (or bordered) design, wherein the card’s edges are a solid color, usually white.

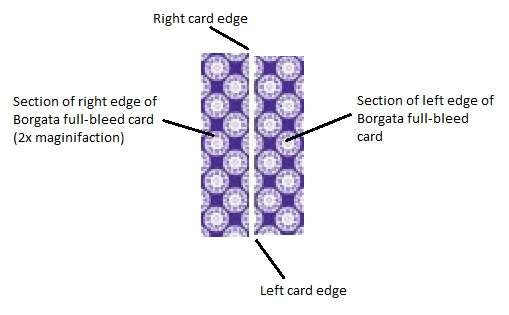

Let’s take portions of the above image, magnify them, and therefore draw attention exactly to the subtle variations that Ivey’s companion, Sun, was allegedly able to spot.

Here’s a look at the top and bottom of the card, magnified 2x, and with the bottom edge brought up to the top and rotated 180 degrees, so it can be compared directly against the top edge. The blurriness is caused by enlarging a computer image and wouldn’t exist in real life, and besides that, it’s irrelevant; the actual edge sorting has to do with seeing how much of the little dot-filled circles are cut off by the edge of the card:

It’s very easy to see that much more of the circles are showing on the top edge of the card than on the bottom edge.

That’s what edge sorting is, in principle, but in the Borgata-v-Ivey matter (and probably in the Ivey-v-Crockfords case as well), the differences may be even more subtle. Most multiple-deck shoes used in casinos show only a bit of one of the side edges of the next card to be brought into play. Here’s an example of a nice, high-end baccarat shoe, from the Fournier brand of card shoes:

By way of disclaimer, note that the pictured Fournier shoe has no connection that I know of to the Borgata-v-Ivey case. (That’s a slick looking shoe, by the way.) I was unable to determine the brand of baccarat shoe being used at the Borgata, but most of the nice card shoes use a similar design, exposing just a portion of one side edge of the next card to be dealt, and image is used as an illustrative example only.

So, while the top/bottom example shown above is a great illustration of how edge sorting works, it’s actually the left and right edges of the Borgata full-bleed card design printed by Gemaco that come into play. Here’s a similar magnification and clarification of edges:

That difference is even harder to see, but it’s there, and that’s what the Borgata alleges that Ivey’s Cheng Yin Sun was able to detect from several feet away, across the baccarat table, while the first card to be dealt in a given hand was still in the shoe.

How the cards got to that state, where the detectable differences along the edges remained consistent and were used to identify the “good” baccarat cards — certainly the nines and eights, but maybe the sevens as well — is the other portion of the claims made against Ivey and Sun.

As we detailed last time out, Ivey and Sun are alleged in the Borgata lawsuit to have requested and received a complex series of conditions before and during game play that allowed those good baccarat cards to be detected, rotated, and returned to the automatic shuffler without being otherwise disturbed in regards to their orientation. They also, allegdely, demanded the same eight-deck shoe be used over and over again, to keep those “lucky” (rotated) cards in play, hand after hand, shoe after shoe.

The above illustrates the principles of how edge sorting is done. Some poker commenters have offered that the practice has been known and implemented by advantage players for decades, and that vastly understates the problem — edge sorting actually details back to the beginnings of playing cards themselves.

Sir John Suckling, the so-called “inventor” of cribbage (another card game this writer is fond of), traveled up and down the length of England in the early 17th century, spreading the word about this great two-person game. It was only later discovered that Sir John was a bit of a scoundrel. Decks of playing cards in those days were hand-printed and hand-cut, and Sir John arranged for some of the key cards in cribbage (fives and others) to be cut either a bit longer or wider than the others in the deck. Since these were all cut by hand anyway, some natural variance was bound to occur, and Suckling made a small fortune, according to lore, by exploiting it. By the 19th century, this process was well known as “longs and shorts,” and yes, you could look it up.

So how does a casino prevent edge sorting? Before I began my career in the poker world, I actually worked with some printing concerns, and have previous experience in these matters, to the point of even once testifying myself in a federal civil case as an independent packaging expert. So I have some familiarity with the topic.

The easiest way is to stay away from elegant, “full bleed” card designs, whose heightened susceptibility to edge sorting has been widely known for generations. Bordered cards might not appear as elegant, but a poorly-cut bordered card or deck is very easy to remove from play.

For full-bleed designs, that’s much more difficult. Repeating designs such as that used on the Borgata cards central to this case aren’t the only element to be considered. Another factor is the trimmed size of the playing cards themselves, and that varies a bit as well.

The so-called “standard” size for American-made and -played poker cards is 2-1/2″ by 3-1/2″, but the trimmed size is just slightly smaller, in the manner that a 2″ x 4″ piece of lumber isn’t really two inches by four inches. And then there are the varying sizes of decks. So-called “bridge” decks are narrower, 2-1/4″ x 3-1/2″, pre-trimmed, and “jumbo” decks are often a bit wider or taller.

Then there’s the matter of the card design. For repeating-background cards, such as these, the way to make the cards as impervious as possible is to identify the length of an individual repeating unit within the card’s background, then print and center that tiny unit during the trimming process.

This is all very difficult to do. For the Borgata cards shown, the individual unit looks like this:

The repeating design stretches from the start of the circle to the start of the next circle, both horizontally and vertically. Since Borgata design is two-dimensionally symmetrical, the repeating design unit is a square… albeit a very small one. Like a tiled floor, if one takes a bunch of little squares outlined as in the above and glues them together, the uniform card-back design is the result.

Here’s the hidden catch: The sides of the square, as illustrated above, have to divide exactly into the trimmed measurements of the finished card, both horizontally and vertically. Otherwise, there’s no way to trim the card so that the design isn’t immediately susceptible to edge identification.

Even designed and measured properly, there’s still another challenge as well in the trimming. The safest way to stop all but the most advanced edge sorting is to split the middle of the largest component of the unit, although some card designs could still have security issues around their rounded corners — though that’s not an issue in this case, where the cards were secreted inside a baccarat shoe and only part of one edge was visible.

Instead, in this case, that meant Gemaco appears to have tried to position the sheets of uncut cards precisely so that the slicers went exactly through the middle of the little circles.

Oh, yeah: Uncut sheets of cards measure a couple of feet across, and even after being coated with plastic, they’re lightweight and flexible. There is almost always some play, some allowance that occurs as the sheets of cards are being cut. The example shown in the Borgata lawsuit filing illustrates a side-to-side variation that doesn’t appear to be more than 1/32″ of an inch. That’s very tiny, given the design, printing and trimming restraints, yet it was allegedly enough for Ivey and Sun to successfully implement it as part of a complex edge-sorting scheme.

Full-bleed cards really shouldn’t be used when money is at stake, and this is why. It’s a lesson that card players and the businesses that serve them are still learning, centuries after the identification of card variations became part of the world of cards itself.

Didn’t understand. So why not to make cards with no patterns, just plain red or green or whatever color?