Future US Online Gambling: A Long Arm Regarding Consumer Embezzlement?

As the US prepares for what appears to be an inevitable and mostly welcome expansion of online gambling, there a still a few questions remaining to be answered regarding what will be expected of participating operators in instances of customer-related fraud and embezzlement. More specifically, what’s going to occur when a problem gambler manages to steal a small fortune and then gamble it away on a newly-US-state-regulated online site?

It’s not a welcome question in some industry quarters, but it is reality, and it’s just as inevitable in the long run as online gambling itself. While many forms of online gambling have been shown to be lower in instances of problem and addictive behavior than their live counterparts (online poker being a prime example), there’s still a non-zero, problem-gambling element.

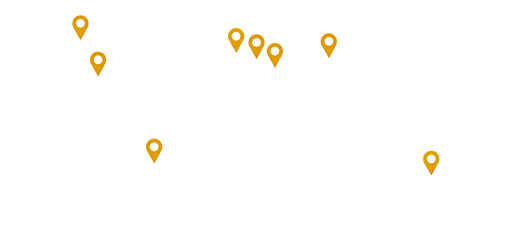

The regulated US sites in New Jersey, Nevada, and Delaware have had a remarkably clean first few years in this regard, bolstered as they’ve been by rigid geolocation protocols and proper ID-verification procedures. Kiddie-gambling stories aren’t likely to be the future bugaboo in the US; that’s all false fear-mongering by anti-gambling forces in general.

Instead, as it’s been in regulated markets overseas, it’ll be the tales of problem gamblers who’ve managed to steal money elsewhere, often from their real-life employers or businesses, then managed to find a way to get the money onto an online site and gamble it away. Those will be the headline grabbers five or ten years down the road.

We need only to look at some of the best-regulated overseas markets to see this occurring. Every few weeks, it seems, there’s a tale emerging from the United Kingdom about some poor mug who managed to siphon six figures out of a business — usually in numerous thefts spread out over a couple of years — then blew it on one or more gambling sites.

The problem hasn’t been geolocation failures or fake IDs. Instead, time and again, online firms doing business in the UK have failed to conduct proper KYC (“Know Your Customer”) checks. In the haste to pull in those deposits, many of these firms just haven’t been too interested in checking into how some bank clerk just happened to have £200,000 to fritter away betting on Premier League matches.

But the UK has been very proactive in using a “long arm” approach, fining operators large amounts in these instances. Those fines included penalties for failing to do proper KYC checks, include some investigative and administrative expenses, but the largest share of these fines has typically been in the form of a repayment back to the victims of the gamblers’ original thefts.

There have been a couple of dozen of these cases just in the past few months, and it’s getting so the UK-facing firms know they’re going to be dinged by the UK’s Gambling Commission. It’s even led to a new development: Leading UK sports book and gambling service William Hill recently made a £500,000 payment to the Dundee (Scotland) City Council in an embezzlement case involving one of the council’s members, Mark Conway.

Conway, described in news reports last year as a “senior IT expert,” used that expertise to siphon £1.065 million from the council’s accounts through a complicated scheme. He then got that most of the money into various gambling accounts and, indeed, gambled it away. Conway was sentenced to prison last year on that part of it.

However, last week’s payment of the £500,000 by William Hill to the Dundee council was unusual, in that it was voluntary; it represented the amount Conway gambled and lost at William Hill. Truth be told, though, the payment likely just saved the UKGC from having to issue a largish fine against the company, as it has in other cases. (There still may be an administrative fine coming in this matter at some point.) The long-armed clawback has become common enough in these cases that it’s now become part of the expected punishment.

William Hill and its largest rival, Ladbrokes, have been involved in more of these clawback fines and penalties from the UKGC than any other firms. Whether that’s a case of the two giants simply having many more customers or having greater KYC issues is a question that can be asked, even if it might be irrelevant. The deeper dig, though, is that the regulated UK gambling industry has implemented a fix of sorts to address some of the third-party harm that can’t be addressed in other ways.

In the US, this sort of long-armed clawback regarding problem gambling and third-party victimization isn’t even on the radar. The closest thing there’s been to a legal clawback effort in a gambling matter was probably the Bradley Ruderman case several years back, in which Ruderman gambled away millions in stolen hedge-fund monies in the celebrity LA poker games that became part of the basis for “Molly’s Game“.

Ruderman was convicted on Ponzi-scheme charges for his original thefts, and attorneys later went after some of the other high-profile participants in those poker games who allegedly won Ruderman’s stolen money. Some of those celebs settled, too, if just to avoid some of the pending bad press.

But, can you name a case where a US-based casino has been ordered to pay back to third-party victims the money stolen by a gambler who then lost large sums on the casino’s floor? I can’t name an example, and I’ve done some searching. Instead, several legal cases exist in the US where the casino has successfully defended against the long-armed clawback on the basis of having a reasonable claim that the casino didn’t know the gambler’s funds had been stolen.

It’s a legit claim for brick-and-mortar gambling, especially given its history and heritage; appearances count. However, whether that will hold true in the online sphere, 10 or 15 years down the road, might be another story altogether. One thing’s for sure: The UK and the US are on entirely different wavelengths on the issue, as William Hill’s voluntary repayment in the Scottish case duly shows. It wouldn’t be at all surprising to see US-facing firms, especially those participating online, to be forced down that same road. It may indeed turn out to be a cost of doing online business.

COMMENTS