Cheaters and Thieves Week: Lusardi/Borgata Lookback 1 — Questionable Surveillance Topic Resurfaces

We’re continuing on with this week’s “Cheaters and Thieves Week” story theme with a couple of looks back at the famed counterfeit-chip cheating incident orchestrated by Christian Lusardi at the Borgata Winter Poker Open in January of 2014. Lusardi himself is the link to theme, even though we’re going to examine a tangent storyline from that cheating affair this time out. It’s a dead-horse beatin’ affair, but a fun one.

Here, we’ll reexamine the methodology used to determine how the final 27 players in that fouled event were to be reimbursed from prize money once all players who had potentially come into contact with Lusardi and his fake chips in that big-field prelim even had been refunded.

Our readers may well remember that months later, the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement, working hand in hand with Borgata, issued its formal ruling for how prize money in that event was to be redistributed. That decision appeared to be inherently unfair to the final 27 players in the event. Six of those players eventually filed a class-action in suit, but lost that case. The Borg’s attorneys argued, rather more successfully, that the payment distribution was just because the tourney itself was fouled the moment Lusardi introduced the first of his fake chips.

Christian Lusardi was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for inserting counterfeit chips into a Borgata poker tournament.

We’ve never argued that point, nor that any entrant who could have come into contact with any stack potentially tainted by Lusardi’s cheating shouldn’t have received a refund. Of course they should. But coming in contact with Lusardi’s fake chips, it turned out, was for the powers that be to declare it akin to a flu bug. Anywhere in the same room was close enough.

In April of 2014, three months before the Borgata succeeded in having the case dismissed, I argued that the DGE’s solution was inherently, mathematically unfair. As part of the DGE-mandated distribution, the Borgata issued full refunds to 2,143 non-cashing players — or rather to non-cashing buy-ins for those players, since this was a re-entry event.

In a press release the Borgata issued about the settlement back then (it’s since been removed from their site), the casino offered these details:

$1,200,080 to 2,143 players who were eliminated from the event short of the money, but who had some chance of coming into competitive contact with the counterfeit chips allegedly introduced by Christian Lusardi, who remains jailed on related charges;

Keep that 2,143-player number in mind. Among the issues the lawsuit attempted to correct was that the refunds were given to way, way too many players, including many hundreds of entrants who literally had no chance of coming into contact with either Lusardi or any other player who might have played at Lusardi’s tables. Yes, tourney tables are broken throughout the day, every day. However, it now seems confirmed that the Borgata, amid its investigation, made little effort to determine the true extent of the table-to-table ripple effect of Lusardi’s cheating.

Think of it this way. To start, Lusardi began play in each of the two flights at a single table, whatever it was. That table must have been immediately fouled, since the Borg’s surveillance (as you’ll see shortly) could not see exactly when he started to insert the fake chips. The IDs of those players should’ve been easily determined. Per other court documents, each player was generally identifiable, including Lusardi, and officials pored over the security footage, trying but failing to determine exactly how and when he snuck the fake chips into play… likely one or two at a time as chances dictated.

However, only when Lusardi’s table broke would other tables in the room (meaning each of the players at those tables) become fouled, and would then warrant refunding. If players from other broken tables were moved to Lusardi’s table first, then only that new player should also have deserved a refund from the cheating.

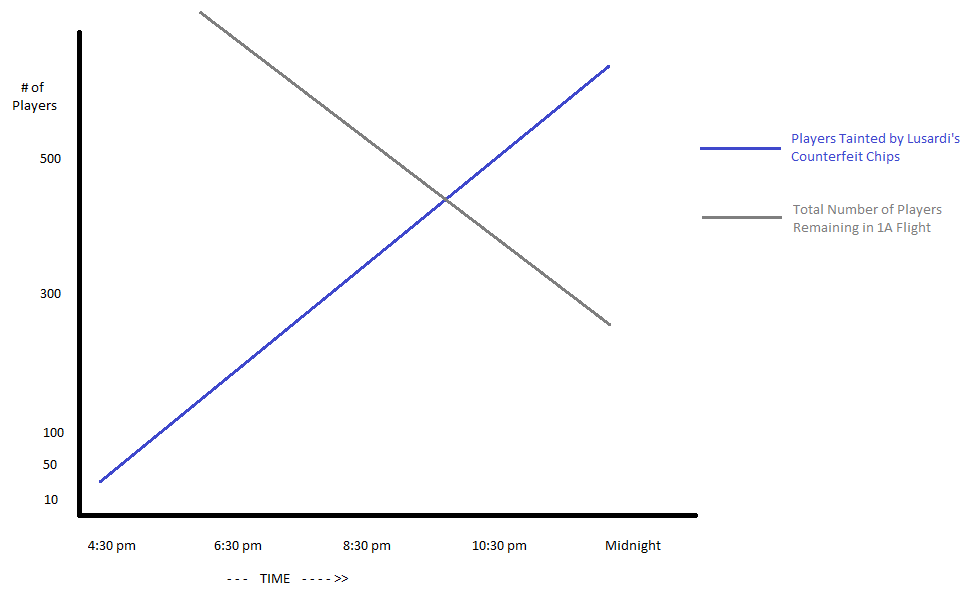

At first, only a tiny portion of the tables in play could have been affected by Lusardi’s cheating. I tried to express it back in 2014 by creating a sample graph (click to enlarge):

However, there was no concrete evidence at the time, just the obvious mathematical surety. Now, though, there’s a bit more, in the form of the opinion in the class-action case that, somehow, still went the Borgata’s way.

Here are some important excerpts (bolding mine):

In a supplemental report, the investigator reviewed the analysis the Division commissioned from Borgata, which listed every player in the tournament, when they played, where they played and where they could have come into contact with Lusardi or the counterfeit chips. As twenty-seven players were still in the tournament at the suspension of play, the tournament ranking included in the analysis listed the 28th through 450th place finishers and the prize money each was awarded before being eliminated.

Having been furnished with the investigative report and tournament analysis of player activity, the Director issued his final order. After noting the Division’s determination “that Borgata was in compliance with the [Casino Control] Act and the regulations promulgated thereunder, specifically regulations related to the conduct of tournaments, and its poker tournament internal controls,” the Director ordered Borgata to pay a total of $50,893 to entrants winning prizes not yet paid at the suspension of play; and to distribute the remaining unpaid prize funds ($1,433,145) and its portion of all entry fees ($288,660), a sum totaling $1,721,805, as follows: $560 to each of 2,143 entrants who may have been affected by contact with counterfeit chips and were eliminated from the tournament without qualifying for a prize; and $19,323 each to the remaining entrants.

More:

The Director [DGE] reasonably chose to divide the entrants into four classes of similarly-situated players: 1) entrants who busted out not playing near Lusardi and not exposed to counterfeit chips; 2) entrants who busted out who might have been exposed to counterfeit chips in play; 3) entrants who won a prize of between $1,082 and $6,338 for placing between 450th and 28th in the tournament, all of whom may have been exposed to counterfeit chips; and 4) the last twenty-seven entrants still in the tournament when play was suspended who would certainly have been exposed to counterfeit chips.

The key phrase therein is “may have been exposed,” which in reality meant, “sitting in the same room.” See, there’s this, from that now-removed Borg presser:

All entrants who played Tuesday, January 14th in Day One-A beginning at 10 am will receive a refund of $560, with the exception of those entrants who played in the Event Center and busted out prior to 4:30 pm, as those entrants could not have come into contact with Lusardi or any of the counterfeit chips he allegedly introduced.

In other words, despite spending two months investigating the cheating incident, the Borgata did no player tracking, from table to table, whatsoever. All they did was turn over the entry lists and initial seating assignments to the DGE. It would have taken a couple or work weeks, in my estimation, to scan available security footage and note people busting or being transferred to another table within Lusardi’s room. One would have had to create a visual chart, showing the tables and seats in that room. Add to that a detailed spreadsheet noting when each player actually busted out and if the steadily increasing, possible presence of Lusardi’s fake chips could’ve reached that player’s table, due to table transfers. Then dig in and watch the security tapes, over and over, as players bust and tabls break.

It would have been a pain in the ass. But it could have been done. And the Borgata, with the DGE’s cooperation or approval, chose not to do it. Instead, they willingly transferred a larger share of the ultimate financial responsibility for the Lusardi’s cheating to the final 27 players. Whether or not the prizes for those final 27 were distributed properly is moot, and the same goes for whether the later class-action case was properly decided. That stuff isn’t relevant to this skimping on effort.

It’s also true enough that the presiding judge likely felt he had to rule in favor of the Borgata. Among other things, as an appellate panel noted that “allowing that case to proceed would undermine the agency’s ability to regulate casino gambling in this State.”

Roughly restated, New Jersey’s court system thus found that the players literally had no cause of action against the casino regarding negligence in a gaming-related matter. Instead, that legal right belongs to the State of New Jersey, and only the State of New Jersey.

So what else could the players have done, against such a stacked legal deck? Beats me. Just as it would anyone else.

COMMENTS