Sheldon Adelson’s Minions: The Bad Poker of James Thackston

If you were a strident anti-gambling group trying to find a way to ban online poker, would you make the centerpiece of your argument a money laundering premise that’s as leaky as the S.S. Minnow? One would think that the Coalition to Stop Internet Gambling, the anti-online-gambling group being funded by Las Vegas Sands and Venetian CEO Sheldon Adelson, would offer a viable, rational argument in support of its own claims.

Instead, courtesy of a rabidly anti-gambling software engineer from Florida named James Thackston, the organization has quickly gone for the preposterous. Thackston, who given his profession should have had enough mathematical education to know better, instead serves as a frontman for a ridiculous money laundering theory involving online poker that’s easy to debunk.

We’ll get to specific examples of James Thackston’s willful numbers-bending later in this feature, but it’s also important to understand their context… or lack thereof. Besides being farfetched in the extreme and ignorant of the realities and methods of real-world money laundering, Thackston’s mathematical claims are so ignorant of the game of poker itself as to shatter his scenario’s claims of legitimacy.

Thackston, who has a decade or more of history as an anti-gambling crusader, first published some of his claims on an old, defunct site called PoliticsOfPoker.com, but has updated and expanded his beliefs, reformatting them onto a new internet offering, UndetectableLaundering.com. The new site features plenty of Thackston’s fear mongering and cult-like claims, and the centerpiece of the site’s “proof” seems to be a ten-hand example of supposed play at an imaginary online poker table, purporting to show how money can be laundered from one player to another via the poker being played.

Thackston pitches this supposed real-world scenario by claiming it’s been played out by a pro card player. To wit: “Each of the 10 pairs of hole cards in each of the 10 hands was played by a professional poker player. The professional was instructed to play the bystander hands as if they had no knowledge of any other hole cards. He was instructed to play the colluding player hands as though the game was under surveillance by both human and automated anti-collusion systems.”

Neither Thackston nor Cheri Jacobus, the right-wing lobbyist hired to foist this garbage in front of as many pairs of eyeballs as possible, will confirm whether or not the supposed “professional poker player” is Floridian Bill Byers, an old-timer whose poker resume indicates that the only forms of poker he plays are “fixed limit” games. Here’s a link to his career listing of recorded tourney cashes, with nary a no-limit showing in the batch. This is an important secondary point, if it is indeed Byers who has supported Thackston’s cause.

Assuming it is Byers who played out Thackston’s fanciful hands, it would explain a lot — and Byers himself will be featured prominently in a subsequent “Adelson’s Minions” post. But as you’ll soon see, whoever the “pro” was who played the hands in Thackston’s example, he knew next to nothing about how no-limit Texas Hold’em is played at high online stakes.

Still, even playing hands very badly — like a “nit,” in poker parlance — is only part of the problem with Thackston’s scenario. Of greater concern is the fact that the cards and hands themselves appear to have been arbitrarily skewed by Thackston in order to create a collective example that seems to support Thackston’s money-laundering claims. It’s the type of thing that would have a research paper jettisoned from consideration by a professional journal, and why none of Thackston’s people appear to have had his work verified via peer review.

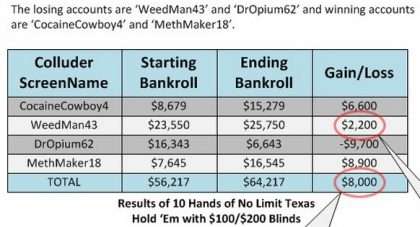

Then again, what would a serious peer review make of player names such as these?

Weedman43, DrOpium62, Cocaine4 and MethMaker18 are just the latest of several such names employed by Thackston in a fear-mongering practice that dates back to his PoliticsOfPoker days. As I’ve noted before, Thackston by his own example proves he’s more suited to make this generation’s version of “Reefer Madness” than he is to offer serious debate on online gambling, but that’s a whole ‘nuther story.

Back to the bad math. Whether or not the skewing stems from Thackston falsifying the hands themselves, or simply comes from extracting selected hands from a larger sample to suit the purposes of his bogus claims, the end result is the same: It’s all a lie.

Let’s have some examples. Note that throughout his scenario, Thackston populates his fictional online poker table with those four humorously named, colluding money launderers, who are joined by six “bystander” players.

Bad Poker #1: Thackston skews the distribution of hole cards received, by eschewing pocket pairs.

In the first nine of the hands in Thackston’s ten-handed scenario, the six “bystander” players receive the grand total of one pocket pair, a hand of 10-10 held by an early-position player who is then forced out of the pot when a queen is flopped. Another of the bystanders somehow has a queen, but is also magically bluffed out of the hand by one of the colluders, who is representing a flush.

In an interesting aside, nowhere in any of Thackston’s scenarios are the innocent bystanders at the table allowed to execute a successful bluff. Even though Thackston’s cheaters are sharing hole-card info among themselves, the other players are also cursed, it seems, by inordinate bad luck: They never hit their flops, their draws never get there, and they invariably get lousy cards. Pretty easy setup for the cheaters, if you ask me.

Nine hands is nothing in poker terms, yet nine hands is enough to show Thackston clearly veering away from reality. The odds of any given player receiving a pocket pair in hold’em for their hole cards, is easy to calculate and widely known: It’s 1 in 17, or 16:1. It’s easy even for a novice to understand — if that novice wants to. Whatever is the first card the novice receives doesn’t matter by itself; it’s whether the second card received is of the same rank. Once that first card (whatever it is), is received, there are 51 other cards, all equally unknown, three of which are of the same rank as the first card the player already has. 3/51 = 1/17, or about 5.9%.

Over the first nine hands, only one of the innocent players at Thackston’s imaginary table receives a pocket pair, and that’s a middling one, out of good position at the table, and he’s forced to fold it by subsequent action. All that can indeed happen, but it’s the collective convenience of this and other happenings that exposes Thackston’s false motives.

So why would Thackston use such a strained sequence of hands in his scenario? The readily apparent explanation is that it’s only such a skewing of probability that he can create the needed opportunities for his money-laundering scenarios to occur. As you’ll see, these are forced bystanders, due to getting abnormally bad cards. But it’s a false skewing; in poker, the cards even out over the long run. That brings other problems within Thackston’s scenario to the fore.

From there it’s on to hand #10, and that’s where it gets funny. Apparently realizing that he’d better balance his faked cards, Thackston then distributes three tiny pocket pairs — 4-4, 6-6 and 8-8 — among the bystander accounts, allows one of them to make a set on the flop (which for novices, means one of the flop’s three cards was a third six). Meanwhile, his colluding cheater accounts fold out of the hand quietly, while the whole hand is described thusly: “Let the Others Take the Pot (Feeding the Anti-Collusion System)”.

As if there was a choice in the matter in real life…. Apparently, the bystanders at the table win hands only when Thackston’s colluders allow them to, regardless of who has the better hand. In the real poker world, sooner rather than later, one of Thackston’s cheaters would end up trapped against a player holding a set such as this, and would lose a big pot. There goes the laundering money, right?

Well, not in Thackston’s world.

Bad Math #2: Thackston further skews the card distribution by giving bystanders few other playable hands

Let’s look at those nine consecutive hands in Thackston’s scenario a little more closely. When we do so, we’ll see that the forced skew has been carried to a ridiculous extreme. Combinations marked including a lower-case “s” indicates that both cards are of the same suit:

ByStander1

A-2, A-7, Q-10, A-K, 10-3, 7-3s, Q-4, 5-2, K-3s

ByStander2

8-7, 9-6, 10-2, J-7, 8-6, 3-2, A-2, J-10s, A-6

ByStander3

10-10, A-5, A-K, K-6, 4-3, J-6, 10-9, J-6, A-Qs, K-Q

ByStander4

K-Q, K-7, 7-6, Q-2, 4-2s, A-7, 10-8, 10-3s, A-10s

ByStander5

Q-3, 4-2s, K-8, J-9s, J-9s, Q-9, 8-7s, 10-8, 9-6s

ByStander6

9-3, J-10, A-6, A-5, A-5, 5-4, 9-2, Q-2, 3-2

In a word, that’s porridge. Two instances of A-K offsuited, one suited A-Q, one suited A-10, a couple of offsuit K-Q occurrences, and one pocket pair (10-10). Two suited connectors, also slightly under expectations (three). But what’s even funnier is that even when Thackston gives his bystander players good cards, he doesn’t let them hit the flop or play them aggressively.

Bad Poker #3: Only by manipulating the hands, giving the bystanders abnormally bad cards and making them play horribly, can James Thackston overcome the problem of the blinds.

The real reason why Thakston and his unspecified “pro poker player” accomplice (probably Byers) have to make the innocent bystander players stink at poker is because that’s the only way to absorb the hidden cost of the game’s small and big blinds — in this case $100 and $200. In a $100/$200 no-limit game, each player must post $300 in blinds every ten hands, and ten hands pass by very fast, usually seven or eight minutes at an online table.

That means that each participating colluder must put $2,000 or more at risk every hour they sit at an online table. For four colluders, that’s $8,000, all subject to a bystander catching some good cards and making off with all the stacks at the table.

How often do good money-laundering opportunities occur? According to Byers’ own letter to the FBI, “In a game of no-limit hold ’em, the 8 shared card values of 4 colluding players will show a favorable, high dollar money transfer opportunity once or twice every hour.” Meanwhile, those blinds keep cycling around, lap after lap.

Is that once-or-twice-per-hour opportunity enough to cover the $8,000 in hourly overhead as depicted in Thackston’s own example? Why would a pack of would-be money launderers even want to risk all the other things involved, such as another player getting hot, or the site that the money laundering is supposedly taking place on discovering the operation, locking the accounts, and seizing all the funds therein?

It makes no sense. It’s easier just to wire the money to a land-based casino and give chips to a money mule in person. Coincidentally, that’s exactly why Sheldon Adelson just paid a $47 million settlement to the US government: Someone laundered money exactly like that — via a bank wire — through the Venetian casino.

Bad Poker #4: James Thackston has the best no-limit players in the world playing like 98-year-old nits.

From here, it’s on to the positively joyous. Thackston positions his imagined online poker money-laundering scenario at a fictional online $100/$200 game, thus making the stakes high enough to make the dollars trading hand feasible to uneducated onlookers.

The truth is radically different. $100/$200 no-limit is an incredibly high-stakes online game, with no more than a couple of hundred participants worldwide, due to the enormous bankrolls needed to sustain a player through the normal variance of the game.

The players who participate in these are often young and hyper-aggressive, with little fear of losing their online bankrolls. They bluff freely and often, though they balance that by carefully selecting a tight range of power hands which they also play quite aggressively.

Thackston’s imaginary bystanders display none of those traits. Instead, these innocent bystanding players meekly limp into unraised pots, fold to the slightest bit of pressure from Thackston’s drug-kingpin colluders when they miss the flop, and in short do everything possible to lose their money and stay out of the way of Thackston’s made-up money laundering game.

As for bluffs by these players, there’s exactly one, a useless river bluff for the last of a small bankroll in Hand 7. This whole hand is a hoot. It starts with one of Thackston’s landerers, CocaineCowboy4, making an opening raise to $500 with A-Q offsuit from middle position. (Throughout the scenario’s ten hands, such under-raises as opening bets are the rule.)

All the other players politely fold. The even more polite and not very aggressive ByStander5 calls from the small blind with 8-7 suited, despite starting the hand with only $4,456. This is patently ridiculous; it might make sense in a limit game, but in a pot where everyone else has folded, the implied pot odds to call here simply don’t exist. It’s so awful it could only have been created by someone who is a fundamentally bad poker no-limit player, and the aforementioned Bill Byers, who may be the self-described “professional poker player” who has been working with Thackston, might be the one who created this farce.

The hand’s high comedy gets even better when the flop comes Ah – Kh – 6s, giving ByStander5 a flush draw. Does he ship his last $4,000 on a semi-bluff? Does he check-raise the expected continuation bet from ol’ CocaineCowboy4? Nope; he meekly checks, and then calls a $1,000 bet. (Eyes roll.) Then, after getting a 9s on the turn, and getting an open-ended straight draw to go with his flush draw, he jams his last $1,956 and gets called by CocaineCowboy4, who is sitting there with A-Q on an A-K-6-9 board.

And of course CocaineCowboy4 would know that even a bad bystander player would have shoved a good pocket pair or A-K pre-flop, having only about eight big blinds (!) to start the hand. Can you say “Autocall”? I knew you could.

Of course, the bystander isn’t allowed to make his hand. The jack of clubs arrives on the river, ByStander5 is busto, and the evil money launderers have scored several thousand bonus dollars from the game in addition to their money laundering, all due to their excellent poker play.

We won’t even make too much of the fact that Thackston and “professional poker player” fucked up the hand’s pretend dollar amounts. ByStander4 should have had $2,956 to shove on the turn, rather than $1,956, not that it dampens the comedy therein in any way.

The best comedies always include a kicker. That comes in the title for this hand within Thackston’s scenario, where he asks, “Does this mean ByStander5” (who lost the hand) “is also a colluder?”

High comedy, indeed.

Bad Poker #5: This imagined $100/$200 no-limit online poker game? It simply doesn’t exist in a form that would allow large packs of money launderers to manipulate it in the way that would make it useful for this purpose.

Truth be told, $100/$200 NL (no-limit) is a very high-stakes online game. As mentioned, only a couple of hundred players participate online at those stakes with any regularity, and for the most part they’re well known to each other.

Given that, the idea that a group of money launderers could somehow create a large number of colluding accounts at these stakes and rampantly dump money to each other without being noticed is… preposterous.

Thackston, who today released an addendum to his site showing four would-be launderers somehow creating 128 different (emphasis his) mule accounts to launder money online, has no idea how immensely difficult it would be to create and fund those accounts, verify IDs, keep healthy six-digit bankrolls in each (which would really be necessary), do the cheating, and somehow keep it from being detected by other skilled players or the sites themselves.

Add in the fact that in real life, those bystanders would be the world’s best online players. The colluders might have an advantage, but it would be narrow, and their team play would be detected quickly.

It’s so far-fetched and ridiculous a concept as to be impossible. It’s technically feasible but it is unworkable in the extreme.

There just aren’t enough of these games at high stakes to make the concept valid. There aren’t that many $100/$200 NL online games, and those that do exist take place on the very largest worldwide sites, such as PokerStars, Full Tilt (now also owned by PokerStars), PartyPoker and a couple of others.

As an example, I’m writing this on Friday night, United States time, which should be prime hours for online play. On the third-largest US-network, the Merge Network, the largest NL cash game currently running is a $3/$6 game — and that’s a six-handed table, with only three players seated.

Over at Bovada, the largest US-facing site, pickings are slightly better: There’s a couple of 6-handed $10/20 NL games running, though each of those has at least one empty seat as well.

So how are 128 mule accounts going to show up at stakes 10 to 30 times higher than anything regularly running, dump money to each other, and somehow not be noticed?

It’s when you think these things through that you realize James Thackston’s money-laundering scenarios are nothing more than surreal fantasy. He has his beliefs and his desires, but all his grandiose efforts are a huge waste of time and effort and, with the support of others, a waste of political capital.

It’s madness.

COMMENTS