Poker Stakers Sue WSOP Main Event Seventh-Place Finisher Nick Marchington

An intriguing lawsuit targeting 10% of the winnings of 2019 WSOP Main Event finisher Nick Marchington is likely to test the boundaries of business law as it pertains to poker staking deals, a widespread practice in the upper echelons of the poker world. Marchington, a 21-year-old Brit who cashed for $1,525,000 in last month’s ME, has been targeted by two primary backers within the C Biscuit Stables staking company and who have asserted in their claim that Marchington did not properly back out of a deal calling for 10% of Marchington’s potential Main Event winnings.

Nebraska’s David Yee and Vancouver, British Columbia’s Colin Hartley filed suit against July 15, 2019, just a day after Marchington busted on the first of three nights of action at the Main Event’s final table. Yee and Hartley are seeking $152,500, representing the 10% of Marchington’s winnings they asserted they had contracted for in an earlier multi-event staking deal agreed on between the two sides, along with additional punitive damages and other costs.

Yee and Hartley, who are represented in the matter by Las Vegas’s high-profile Chesnoff & Schonfeld legal firm, also sought a temporary restraining order and permanent injunction to prevent Marchington from claiming the disputed $152,500 portion of his larger winnings. Caesars, the parent company of the WSOP, had issued a check to Marchington for those winnings but quickly issued a stop payment after being notified of the lawsuit. Marchington has since forwarded the check to his own attorneys, Ronald Green and Maurice “Mac’ Verstandig, for possible deposit into a trust account to await resolution of the matter pending court approval.

In late May, Marchington approached C Biscuit’s Yee and Hartley about backing some of his WSOP action, and they quickly agreed to a deal. That deal included 10% stakes in Event #70, $5,000 NLHE 6-Handed, at a 1.1 markup, and in Event #73, the $10,000 Main Event, at a 1.2 markup.

In late May, Marchington approached C Biscuit’s Yee and Hartley about backing some of his WSOP action, and they quickly agreed to a deal. That deal included 10% stakes in Event #70, $5,000 NLHE 6-Handed, at a 1.1 markup, and in Event #73, the $10,000 Main Event, at a 1.2 markup.

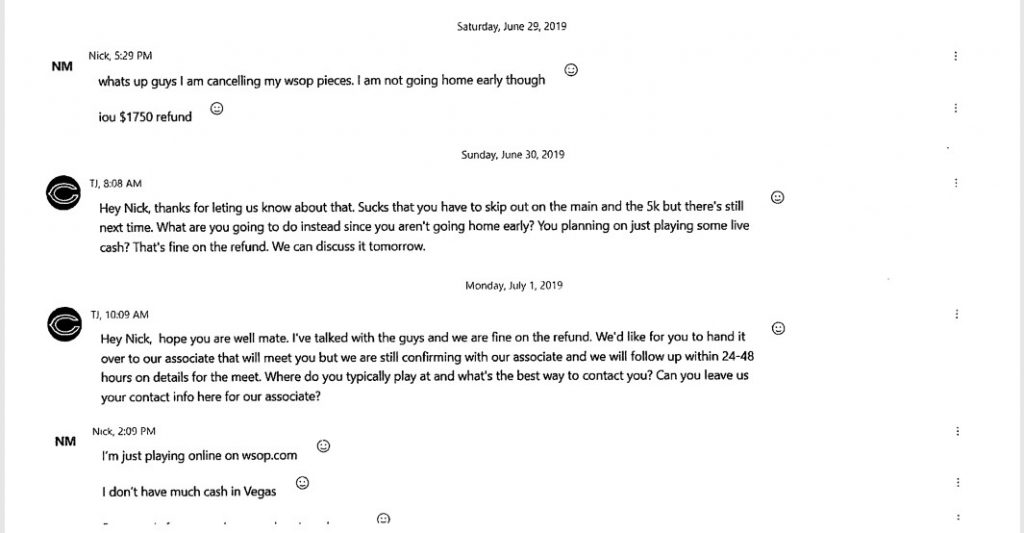

However, on July 29, Nick Marchington notified Yee and Hartley of his intent to cancel their backing deal for those two events, due to a poor summer of results prior to that point. Marchington had hinted at that likelihood one day earlier. Yee and Hartley agreed, and the two sides sought a way to transact a refund. The C Stable backers may have looked for cash, but a cash-poor Marchington sought to push back the refund until he could return funds via transfer on PokerStars, the same method Yee and Hartley had used to send Marchington the original stakes of $875 each, comprised of $275 each for Event #70 and $600 each for the ME.

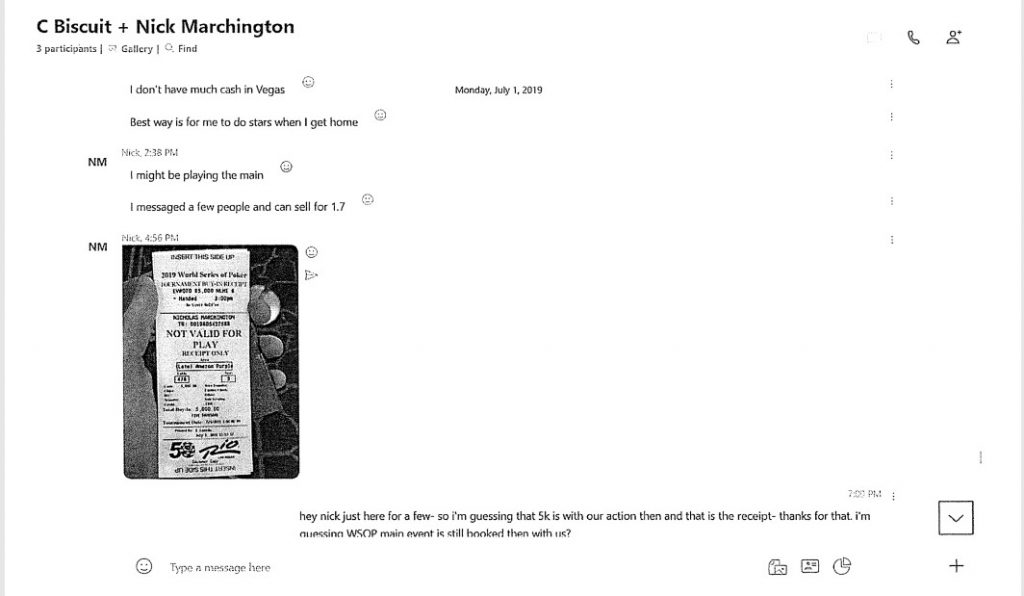

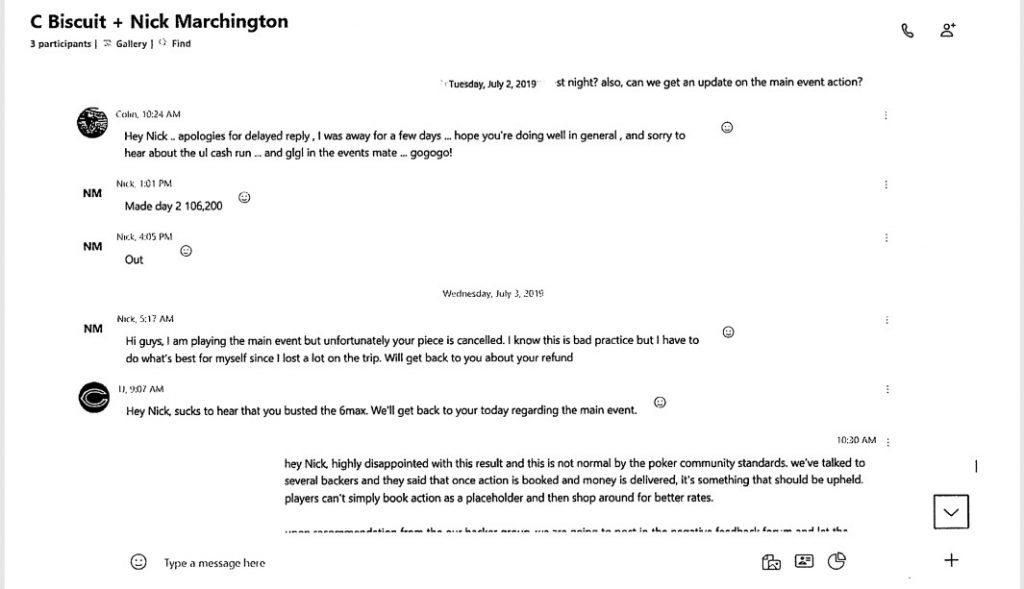

Then communications broke down between the two sides as Marchington seemingly obtained additional backing — and at higher markup — that would allow him to play in both Events #70 and #73. Whether a formal “re-backing” agreement for Event #70 was reached is not entirely clear from a noncontinuous series of text-message exchanges between Marchington and the plaintiffs submitted as court exhibits. However, Marchington sent the C Biscuit backers an image of his Event #70 buy-in on July 1st. That image was sent over two hours after Marchington had texted, “I might be playing the main. I messaged a few people and can sell for 1.7.”

One of the C Biscuit backers, most likely Yee, responded with, “hey nick just here for a few – so i’m guessing that 5k is with our action then- thanks for that. i’m guessing WSOP main event is still booked then with us?

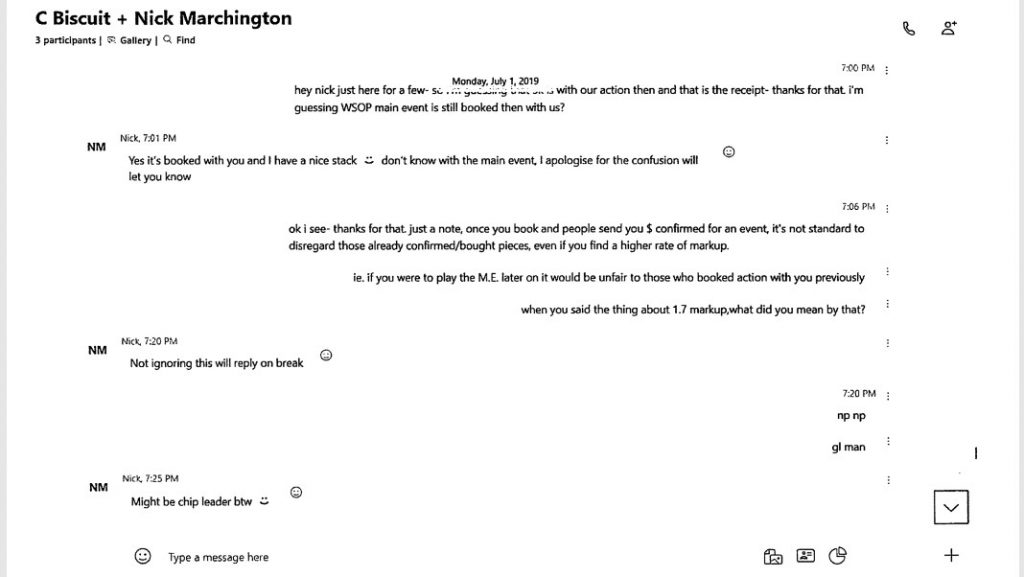

Marchington responded, “Yes it’s booked with you and I have a nice stack. 🙂 don’t know with the main event, I apologise for the confusion will let you know.” Marchington’s text is inexact but seems to indicate a Main Event deal was not in effect.

By this point the C Biscuit backers were likely on full blast, having agreed to back out of the original Main Event deal at 1.2 markup, then being reapproached for the same slice at 1.7, all while still waiting on a refund of the original $1,200 they were still due.

The backer, probably Yee, responded, “ok I see – thanks for that. Just a note, once you book and people send you $ confirmed for an event, it’s not standard to disregard those already confirmed/bought pieces, even if you find a higher rate of markup. … i.e. if you were to play the M.E. later on, it would be unfair to those who booked action with you previously.”

But, given that the two sides had previously agreed to cancel the previous 1.2-markup deal, did a Main Event backing deal still exist? That’s the key defense point. “Requiring a player to enter an event on a given stake would be illegal,” said Marchington’s counsel, Green. “He has the necessary free will to exit the arrangement at any time.”

“It is disappointing to see a backing operation argue a player does not have the right to cancel a stake before a poker tournament starts, especially after accepting the player’s refund,” added Verstandig. “However, we look forward to pursuing this case in the courts, and have faith the court system will bring justice to Mr. Marchington.”

Notice that there’s a difference between something being scummy and unethical and being illegal, and the difference between the two couldn’t be more clearly illustrated than by Marchington’s actions. Yet he appears to be an odds-on favorite to prevail, because no deal appears to have been agreed upon when Marchington started play in the Main Event’ July 2 Day 1B starting flight.

There also are some issues with the text-message exchanges submitted by Yee and Hartley. The court will likely decide on whether the deal existed by examining these exchanges in addition to testimony and other evidence. Four pages, comprising Exhibits H and I, will likely prove pivotal in the matter. Here are these key submissions:

Exhibit H

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Exhibit I

Page 37

Now that you’ve seen and digested them, note that they may omit other portions of the days-long text exchange between the three men. The discussion on p. 35 ends on the evening of July 1, while the text on p.37 of the legal complaint takes place on July 3. That this page was submitted as a separate exhibit means the at least one (and, more than likely, several) pages of the exchange between the three litigants was intentionally omitted from being included in the exhibits.

One is left to wonder why such likely relevant text wouldn’t have been included here, since at least one page worth of exchange had to have occurred, and it’s highly unlikely that it wouldn’t have been ongoing talk about the disputed Main Event backing.

It’s also worth mentioning that the last exchange on the p. 37 clearly cuts off midway the text from Yee. While not all the words of the bottom line can be fully reconstructed, but it appears to read, “[] recommendation from the [] backer group, we are going to post in the negative feedback forum and let the…” That appears to be an attempt to apply pressure on Marchington to adhere to the terms of the earlier 1.2 backing deal.

As part of its just-launched defense, Marchington’s counsel Verstandig has also obtained affidavits from a half-dozen pros he’s represented in prior litigation. Each of those pros has attested to this excerpted statement:

6. It is my understanding of the staking industry that any poker player can cancel any staking arrangement, at any time before a given poker event starts, by simply giving notice of his/her intent to cancel and then refunding the monies as soon as may be practicable.

7. While cancelling staking agreements is often perceived as impolite and discourteous, it is generally understood as being permissible in nature.

Copies of a statement affirming the above element of a staking deal were submitted by Matt Glantz, Matthew Stout, Jonathan Little, Barry Woods, Jason Bral, and YouStake founder Scott Hansbury. However, the pros did not specifically “vouch” for Marchington, as stated in the LVRJ report.

It also leads to a question raised by Marchington’s counsel in its initial response to the complaint, which has also been obtained by Flushdraw. The C Biscuit backers originally agreed to accept a refund, though that was delayed by Marchington’s lack of immediate cash. Yet agreeing to the refund in principle is itself a contractual obligation.

From the defense response: “That C. Biscuit accepted the refund is revealing unto itself. This suit was brought only once Mr. Marchington won a significant sum of money in the Main Event; it seems highly unlikely C. Biscuit would have dispatched another associate to return Mr. Marchington’s refund had he not won any monies in the Main Event and, instead, simply lost his entry fee. Or, stated otherwise, it certainly appears C. Biscuit was at peace with the agreement being cancelled and a refund being collected, until such a time as it realized the agreement would have been lucrative in nature.”

None of these people are likely to emerge from this episode with shining reputations intact, and Nick Marchington in particular will suffer due to what was frankly an unethical choice. (C Biscuit’s ethos or lack thereof will be more fully determined if and when the full body of deal-related communications is publicly known.) He might have done a legal thing, but he didn’t do the proper thing. In a court of law, though, that’s not what matters.

COMMENTS